by Cullen Couch

(UVA Lawyer, Fall 2014)

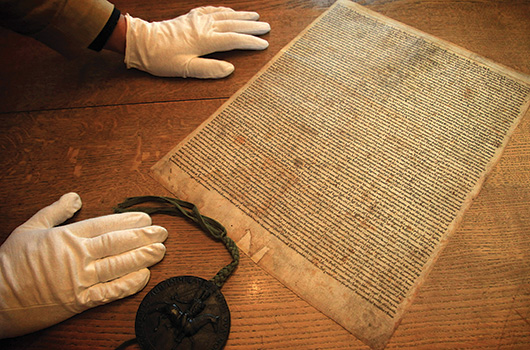

Salisbury Cathedral's Magna Carta

They say that to do injustice is, by nature, good; to suffer injustice, evil; but that the evil is greater than the good. And so when men have both done and suffered injustice and have had experience of both, not being able to avoid the one and obtain the other, they think that they had better agree among themselves to have neither. —THE REPUBLIC, Plato (360 BC)

39– No freeman shall be taken, imprisoned, disseized, outlawed, banished, or any way destroyed, nor will We proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgment of his Peers or by the Law of the land.

40– To no one will We sell, to none will We deny or delay, right or justice. —MAGNA CARTA (AD 1215)

In June 2015 Magna Carta will turn 800. Its age alone is a wonder. Only by a lucky accident of history did it survive the bloody tumult of its birth, and then centuries of war, revolution, and political upheaval. Magna Carta’s animating principles, derived from ancient concepts of justice, evolved to become the totem for the rule of law in an empire that spanned the globe.

In the 17th century, America’s colonists found in Magna Carta a guarantee. They built legal arguments to redeem it. In the 18th century they fought a war to implement it and wrote a constitution to embed its ideals in a uniquely American form of government. In the 20th century, they stored an early copy of Magna Carta for safekeeping at Fort Knox during World War II. The surviving written copies of the original Charter now reside in damage-proof viewing boxes in Lincoln Cathedral, Salisbury Cathedral, and the British Library, where viewers find inspiration, just as our Bill of Rights to the U.S. Constitution found its inspiration centuries ago.

Magna Carta continues to inspire. Researchers at King’s College London are re-examining rival versions of clauses proposed but ultimately rejected during the negotiations at Runnymede, casting new light on Magna Carta’s meaning. Just this past July a committee of the House of Commons published a report, “A New Magna Carta,” in response to a parliamentary inquiry into the question of a written constitution. And Carlyle Group CEO David Rubenstein paid $21.8 million to own one of the four existing copies.

A. E. Dick Howard ’61, White Burkett Miller Professor of Law and Public Affairs and a noted authority on Magna Carta, is advising the Library of Congress on its forthcoming exhibit, “Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor.” In 2015 Howard will give lectures in London under the auspices of the American Embassy, and will lecture at Oxford’s Bodleian Library, at Salisbury Cathedral (which has one of the four extant copies of the 1215 Charter) and elsewhere in England.

“The 800th anniversary is not so much about celebrating Magna Carta’s origins as it is about explaining how and why the Charter survived and what its legacy is for our time,” he says. “Magna Carta could have died entirely, and yet it didn’t. Instead, it has become a universal symbol of the rule of law, of due process of law, and of limits on government power.”

“Given by Our hand in the meadow which is called Runnymede …”

Magna Carta arose out of the chaotic reign of King John whose profligacy, inept statecraft, and military incompetence had infuriated his barons. Forced by the barons’ might and lacking any popular support, John agreed in 1215 at Runnymede to 63 “chapters” that granted “to all the free men of our realm for ourselves and our heirs for ever, all the liberties written below.”

Almost immediately, John sought to have Magna Carta annulled, and Pope Innocent III issued a papal bull declaring it “null and void of all validity for ever.” The deceit of John and an irate Pope came close to smothering Magna Carta in its crib, but the king died in 1216 of dysentery and a young Henry III succeeded him. Henry’s regents, needing the barons’ support, reissued Magna Carta in 1216 (and again in 1217 and 1225). In 1297 Edward I entered Magna Carta into the statutes of the realm.

An engraved 19th century illustration of King John signing the Magna Carta

It continued to evolve over the centuries through statutory amendments and royal proclamations, some repealing its feudal anachronisms, others restating its fundamental principles (just four of the original chapters remain today—the last few were repealed in 1971).

Magna Carta lay largely dormant during the Tudor period. It was in the seventeenth century that the Stuart kings’ notions of “divine right” brought renewed reliance on the Charter. Sir Edward Coke, the greatest jurist of his time, brought forth Magna Carta as authority for his opposition to the Stuart claims of royal prerogative.

Meanwhile, colonial charter companies were assuring prospective settlers that they would enjoy in America the same rights and privileges of their homeland, understood by them to mean the principles contained in Magna Carta for justice according to “the law of the land.”

Originalism and Historical Meaning

Were the barons who forced a tyrannical king to sign the document thinking of timeless values? No. Were they trying to establish fundamental rights for all? Certainly not. Were their words open to interpretation? Absolutely, and therein hangs a tale.

“It was a bargain struck between King John and the barons who had their own interest at heart,” says Howard. “They were not concerned about posterity, and they certainly weren’t concerned about the common good. A very reluctant King John sealed the document. He would have surely broken his promises. He never intended to keep them.”

Ted White, David and Mary Harrison Distinguished Professor of Law, agrees: “It is less a charter of individual liberties than a rebellion against absolute powers of the monarch by a group of persons interested in preserving their own economic and political and social autonomy against the Crown.”

“Magna Carta was intended to give relief to a handful of angry male barons, but the word ‘barons’ was changed to ‘any freeman,’ and that made all the difference in law,” says Suzelle Smith ’83, co-founder of litigation boutique Howarth & Smith, a visiting fellow at Lady Margaret Hall at Oxford, and an elected fellow and member of the board of directors of the International Academy of Trial Lawyers. “In 1215, there were very few ‘freemen.’ But as time passed, the clause was applied in England to guarantee ‘due process of law’ universally, including to women.”

What Magna Carta’s provisions mean, taking into account their context, is not the same as what Coke understood them to mean when he fashioned his arguments against the Stuart claims. “But the language is broad and a potential source of authority to be interpreted in purposive ways by subsequent interpreters,” says White. “That dimension of Magna Carta can’t be underestimated. It is out there as a legacy of a kind, even though its meaning may not be obvious.”

Magna Carta is interesting for what it meant at the time it was adopted and how it summed up important principles, but its modern legacy flows in part from the uses made of it by later generations. “Magna Carta has been glossed in a way that John or the barons in the 13th century might not recognize,” says Howard, who sees “due process of law” as the actual textual connection between Magna Carta and the U.S. Constitution. The phrase “law of the land” in English history very quickly became interchangeable with due process.

“They’re the same concept,” he says. “Due process has been perhaps the most powerful single organic concept in constitutional law. Throughout the centuries people have poured their contemporary understandings into what due process is all about.

“If I wanted to respect the so-called ‘original meaning’ interpretation of the Constitution, I could argue that, when the framers used the phrase ‘due process of law,’ they understood it to be a constantly evolving concept.” Unfortunately, the framers of the Constitution never made explicit how they wanted future generations to interpret their document; or put another way, their original intent about original intent. But we know they had a perspective framed by deep study of the rise and fall of governments and civilizations.

The American Bar Association’s Magna Carta Memorial at Runnymede.

“We tend to think of historical change as a qualitative development over time so that the meaning of a provision one day might not be the same at a later date in a different context,” says White. “But the framers’ perception was different. They saw history as a cyclical process that approximates the human condition going from early life to maturity to decay and ultimately disintegration. It’s not progressive change. It’s not qualitative change. Instead, it is the recurrence of fundamental principles as the course of a nation’s history evolves.”

When Chief Justice Marshall wrote in McCulloch v. Maryland that the Constitution is designed to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs, he wasn’t saying that the meaning of the Constitution would change over time. “Instead,” says White, “he meant that the foundational principles of the Constitution will need to be restated in different contexts as the context emerges. The crises that require constitutional interpretation are products of changed circumstances, and the interpreter is supposed to solve those problems by restating the original foundational principles. The problem is that that view of history has been abandoned for over a century.”

The Law of the Land in England

While the bones and sinew of Magna Carta dealt with the immediate and specific grievances of the barons in their feudal role, the heart and soul of the document is its Chapters 39 and 40. Those fifty words became the cornerstone of English common law, a nascent form of what would later inform part of the U.S. Constitution. But it took a long time and many turns to get there.

What does Magna Carta mean by “the Law of the land”? It doesn’t say, but over time it became consistent with the idea of the right to trial by jury of one’s peers, to confront accusers, and to appeal. “That’s important because you could imagine in a monarchy that there is no appeal, that everything is done at the pleasure of the monarch,” says White.

Later, in 1368, a statute of Edward III said if a law was in conflict with Magna Carta, it should be “holding for none,” or null and void, essentially treating Magna Carta as a “superstatute, in other words, as a constitution,” says Howard. “It didn’t turn out to be Marbury v. Madison. England still has Parliamentary supremacy, and they don’t have what we call judicial review, but the idea gets planted.”

But it was the ascent of the Stuart dynasty with James I in 1603 that became a “pivot point” in England and America that refined the meaning of “Law of the land.” The new king’s claim of divine right was clearly not a Parliamentary principle and was not consistent with English constitutional traditions.

Penumbras and emanations, brawlers and vagabonds: In researching her book on vagrancy law Professor Risa Goluboff came across a revealing artifact in the substantive due process debate in the mid-20th century U.S. Supreme Court.

In response, Parliament passed a series of acts, particularly the English Bill of Rights, which introduced principles beyond those found in Magna Carta. “Coke and his friends argued that Magna Carta laid down certain precepts which they built upon and enlarged in the quarrels between Parliament and the Crown,” says Howard.

“So, yes, you do have some open-ended language in Magna Carta,” says White, “but it is plain that at the time the United States declared independence from Great Britain, the British citizens did not have a full panoply of individual rights against the Crown. In fact, the Crown and Parliament are still dominant. The lawmaking authority in England is statutory. The British don’t have separation of powers in the full sense that the Americans do, so I think Magna Carta is susceptible of over-generalization.”

Smith notes another glaring difference. “The bedrock of American judicial process, the Constitutional right to a jury of one’s Peers, is straight from Magna Carta. Yet, the English, with no formal written Constitution, have virtually eliminated the right to a jury in civil cases.”

The Law of the Land in America

While Coke was leading the opposition to the Stuarts in England, the first English-speaking colonies were being planted in America, beginning with Virginia in 1607. The colonial charters introduced principles of Magna Carta by promising that those settlers who immigrated to Virginia would enjoy all the rights they would have had in England.

The promises helped soothe fears that the charter company would become a monarchical fiefdom with absolute power over them if they chose to settle in the new world. Still, “the theory was that these colonies ultimately would be governed by England,” says White, “so these provisions referencing Magna Carta were likely intended to be rhetorical.”

However, the Crown barely governed at all during the time between the original settlements in the early 17th century and the movement for independence that began in the 1750s. The colonies essentially governed themselves during this long period of “benign neglect” by Great Britain. “By the time that Great Britain attempted to tighten the administrative screws and raise some money [the stamp tax] after the end of the Seven Years War [in 1765], the barn door had been left open too long,” says White. “The colonists had grown used to the freedom to conduct their affairs economically, and to some extent politically, so this was deeply resented,” all of which ultimately led to war and separation.

Magna Carta Moves Temporarily to the Sidelines

After the Revolution, the new government became hopelessly gridlocked under the ineffective Articles of Confederation. Delegates from the 13 states met at the Philadelphia Convention to repair the Articles. But instead they created a new Constitution, which in manifest ways was fresh legal terrain. The frame of government went beyond anything the barons and King John were trying to accomplish, and they had no models to follow. “We are in a wilderness without a single footstep to guide us,” Madison wrote to Thomas Jefferson. “Our successors will have an easier task.”

“The issue in the 13th century and the 17th century was competing notions of who had what power within an existing government,” says Howard. “Nobody was trying to create a new government. In writing the federal Constitution, Americans were exploring new territory.”

Magna Carta resurfaced after the Philadelphia Convention, says Howard. The convention had rejected the proposal that the Constitution include a Bill of Rights. The Anti-Federalists charged that the federal government would be too powerful and threaten civil liberties. “The Federalists realized that they had a problem on their hands so they made the implicit promise that, if the states would ratify the Constitution, the first Congress would move to add a Bill of Rights.”

The political debate that followed was not about civil rights or civil liberties in the modern sense, according to White. The supporters of the 1789 Constitution realized they needed to sell a document that restricted the power of the states more than ever before.

“The debate about the Constitution is really about whether there should be a unit of government, including a judicial branch, that restrains the power of the state legislatures,” he says. “One of the things they do in the Federalist Papers is create this idea that sovereignty resides in the people, so it’s not a matter of transferring power from one set of elites to another. The people were the ultimate sovereign. But that was a rhetorical strategy, not a representation of the reality of American political culture at the time.”

If the Articles of Confederation did anything, they proved that the new country badly needed a stronger central government. “Madison was absolutely right in his diagnosis of the problem: that the states left to their own devices would be prey to European powers,” says Howard. “We had to have a functional central government.”

But the Anti-Federalists struck the cautionary note about the temptations of power and threat to liberty from a strong central government that still ignites debate today. “This has been a process of confrontation and cross-examination in debates over what’s the right balance,” says Howard. “It tends to swing back and forth, but I find it a fundamentally healthy process that began with the Federalists and Anti-Federalists.”

Only in America

The American contribution to constitutionalism, and what makes it distinctly American, arose from its several generations of colonial self-government in an environment abundant with natural resources and conducive to explosive economic growth.

White doesn’t find any comparable episode in the history of colonialism where a colony is given that much autonomy to regulate itself at the same time that it becomes prosperous. “When the British attempted to reassert authority, they were confronting 200 years of American history that tilted in the direction of autonomy for residents of America,” he says. “The British found themselves up against a powerful and singular historical experience.”

Thomas Jefferson’s copy of Edward Coke’s The Second Part of the Institutes of the Laws of Englandat the Library of Congress.

Moreover, while building the framework of their local governments, the colonial “creole elites” (third- or more generation settler families) had been listening to Lord Coke’s arguments. His foundational set of treatises, Institutes of the Lawes of England, overwhelmingly populated their libraries. They had time to develop powerful legal arguments supporting their cause.

The American innovation that the authority for government flows directly from the people emerged from the structural necessity of the moment. They needed government. It follows naturally that in forming that government the colonists intended to retain their inherent fundamental rights within it.

“One way of understanding American constitutional law is to realize that it flows from a common law tradition,” says Howard. “It’s not simply legislation. It is organic and has deep roots in English and American constitutional history. It evolves. It’s dynamic. It becomes, to borrow a phrase that today is very controversial, a living Constitution.”

The Stamp Act, the first time that Parliament had tried to impose an internal tax in America, outraged the colonists. They fashioned resolutions and tracts and pamphlets, repeatedly invoking Magna Carta. Echoing Coke, they argued that their ancestors had been promised the rights of Englishmen as found in Magna Carta, and that the tax violated its principles. “Magna Carta was front and center in this battle with the Parliament and the Crown,” says Howard.

Coke’s authority, the rhetoric of the creole elites, and the language in the charters themselves ultimately gave rise to the unique American insistence on a written Constitution based on concepts of natural law, common law, and the English constitutional system, sometimes pulling together and at other times apart, and still controversial today.

A “Baffling” Form of Government

It’s difficult to explain American constitutionalism to Europeans, says Howard. “The English don’t understand federalism because the notion that you can have dual sovereignties escapes them. Our mix of practices and ideas is also baffling to many people in other countries.

“American constitutional law has a dialectical quality. It’s a conversation among people, most of whom share some basic assumptions about liberty and freedom and order but have often very conflicting views of how to make it work.”

The American fealty to a written Constitution, partly British and partly American, comes from a long tradition of putting in writing documents reflecting the terms and balance of government power, from Magna Carta through the Petition of Right and the English Bill of Rights to the colonial charters and state constitutions.

“We like to look at a text and say, ‘There’s the answer,’” says Howard. “There’s a certain comfort in the assurance of the written word. But we also carry unwritten ideas about inherent rights, fundamental rights, natural law. We put different labels on them, and a dualism between the written and unwritten continues.”

Further, and particularly in New England, colonial Congregationalists and Presbyterians added to the mix their ideas about covenant theology. Originating in Europe and Scotland, covenant theology was based on a voluntary association between members of a congregation who make a compact between each other and with God. Covenant theology developed its modern form in New England in the 17th century, and the Constitution took on some of its flavor, says Howard.

Visitors tour the Library of Congress new exhibit, Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor, in Washington, D.C.

“I think it helps explains how, when the American Civil War erupted, the North had become committed to the notion of the Constitution as a covenant of the people that you couldn’t rip apart,” says Howard. “In the South, John C. Calhoun’s compact theory claimed that the states had made the Constitution and were free to leave it. These two fundamentally different ways of thinking about the Constitution are highlighted by the religious fervor of the North in the Civil War. Think of the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic,’ that God was part of this plan.”

“There are many people today who will tell you that the Constitution was divinely inspired; that is distinctively American,” says Howard. “In most parts of the world, constitutions are thought to be useful but certainly not divine. They don’t have the enduring quality that the American Constitution has had.”

Still a Touchstone

Or that Magna Carta still has today. “It would be interesting to do a formal count of how many times Magna Carta has been cited in state and federal opinions,” says Smith. “My guess is hundreds of times. Magna Carta has been referenced as the keystone of the rule of law in many significant opinions in the 21st Century.”

In 2003 Justice O’Connor calculated that the Supreme Court alone had cited Magna Carta 50 times in the past 40 years. In Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, the 2004 case involving the holding of suspected terrorists indefinitely without charge or trial, they would do it again. Justice Souter wrote, in partial concurrence and partial dissent:

‘[W]e are heirs to a tradition voiced 800 years ago by Magna Carta, which on the barons’ insistence, confined executive power by ‘the law of the land.’”

Later in Boumediene v. Bush, another detainee rights case, Justice Kennedy wrote for the majority:

Magna Carta decreed that no man would be imprisoned contrary to the law of the land. Important as the principle was, the Barons at Runnymede prescribed no specific legal process to enforce it. [G]radually the writ of habeas corpus became the means by which the promise of Magna Carta was fulfilled.

And he linked it directly to Article I of the U.S. Constitution:

The Framers viewed freedom from unlawful restraint as a fundamental precept of liberty, and they understood the writ of habeas corpus as a vital instrument to secure that freedom. Experience taught, however, that the common-law writ all too often had been insufficient to guard against the abuse of monarchial power. That history counseled the necessity for specific language in the Constitution to secure the writ and ensure its place in our legal system.

Aside from the Supreme Court, politicians and activists of all stripes from the earliest days of the Republic to this day, from the right and the left, have used Magna Carta as a tool to support very different understandings of what “liberty” and “freedom” mean.

“Curiously, I think we have made more use of Magna Carta’s legacy and symbolism in this country than they have in England, where it was first written,” says Howard.

Smith agrees. “My sense is that Americans, led by the Founding Fathers may have an even stronger reverence than the British for Magna Carta,” she says. “Our dedication to restrictions on government and protection of individual liberty by law is more a part of our societal structure than in Britain.”

If symbols mean anything, then Magna Carta really does mean more to Americans, and understandably so. The settlers leveraged it to build a working government and the framers to build a republic. So it is fitting that the only monument built at the Magna Carta memorial at Runnymede, a white portico cupola in the meadow by the Thames and a short royal barge trip from London, came courtesy of the American Bar Association in 1957. So happy 800th, Magna Carta. America might have been a very different nation without you.