(The National Law Journal)

Data explosion and complexity of cases require greater division of labor.

Joe Yanny was aghast.

The veteran entertainment lawyer, whose clients include Paula Abdul and Grateful Dead Productions, was reacting to the suggestion that he comes across in the courtroom as a bit of a Lone Ranger – a solitary crusader in the mold of Clarence Darrow, Louis Nizer or these days, Gerry Spence.

"Who, me?" asks Mr. Yanny of Los Angeles Fischback, Perlstein Lieberman & Yanny. "To the contrary, I find that more and more I’m spinning courtroom work off to my colleagues."

While a lawyer might have to share the courtroom glory getting a little help on a case is proving a pretty good strategic move in the 1990s. The ideal of the lone legal eagle is out. Teamwork is in.

The rise of this "committee" effort may reflect the zeitgeist of a nation feeling communal as the century draws to a close. Or it may have been influenced by the recent impressive victories of high-profile tams, such as OJ Simpson’s defenders. But lawyers of all stripes have more practical reasons for coming to believe two, three or a dozen heads are better than one.

The length of time it takes to try a case nowadays is also a factor.

"When I started practicing law, important cases ran a week or so," says Don Howarth, of Los Angeles’ Howarth & Smith, who lectures for the California State Bar on trial strategy for plaintiffs. "The trial my partner and I just completed went three months and had a total of 22 witnesses. No one can be up, everyday, for three months."

Sharing the limelight

Not that Mr. Black has so embraced the team concept that all this talent makes an appearance at trial. He routinely gives the opening and closing as well as the key examinations – "unless I think someone is uniquely qualified to do it better. Say, if it’s a cross on DNA, I’ll gladly defer to Barry Scheck, "he says in a laughing reference to the professor in the law clinic of New York’s Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, Yeshiva University, who became a household name for his work on the Simpson defense.

Similarly, Mr. Winterman says he bows out of his customary starring role in favor of a "guest attorney" who combines specialized knowledge with advocacy skills – as when he used someone who was up on the psychological literature to help defend a medical malpractice case with a brain-damaged child.

There is a risk, however, to these cameo appearances Mr. Howarth cautions that a long case develops its own conventions and in-jokes that may befuddle a jury. "You bring in a stranger, however knowledgeable," he says, "and when he’s through and goes away, the jury is apt to be left thinking, ‘What was that all about?’"

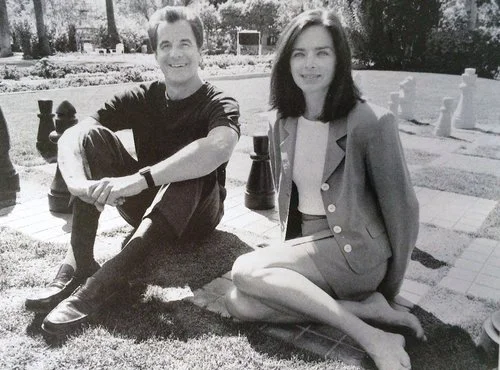

Instead, the Harvard-trained litigator assumes he and Ms. Smith are interchangeable on subject matter. They divide up the trial work based on their physical differences. When examining a dying client on the stand about what terminal cancer had done to his quality of life, the petite Ms. Smith "had finesse and gentleness, almost like a hostess," he recalls. "If I’d done it, given the taboos we have in our society about death and dying, I would have come across as brusque and stilted or both."